I learnt something new this year about the day before Diwali/Kali Pujo. Bangalis apparently celebrate it — I say apparently, because (shamefully enough) this was the first time I had heard of it — as Bhoot Chaturdashi. Given the very rough colloquial translation, as “the fourteenth day [of the lunar fortnight], of ghosts,” the occasion feels almost tailor-made for all sorts of funny posts on social media.

But bhoot also means ‘the past’ (just like kaal means time as well as death or distress). As one commentator put it, multiple meanings of the word leave the occasion up to many interpretations. But two observances remain common. On that day, believers honour the spirits of fourteen generations of ancestors by lighting an equal number of lamps in the evening. They also consume a savoury lightly-fried dish made with fourteen (!) specific kinds of greens. In spirit — yes, I couldn’t resist — Bhoot Chaturdashi is more Día de los Muertos, interestingly also celebrated (roughly) around the same time, and less Halloween.

Though who knows what the exact, exhaustive, protocol is for the occasion, if any. Ma excitedly claims you should also keep a (new) broom near the main entrance to your home to chase (presumably less-than-friendly) spirits away. Meanwhile, perennially sceptical Bapi is convinced the fourteen-greens pre-mix sold in his neighbourhood market in Kolkata has five kinds instead, unscrupulously mixed with random leaves to fleece the gullible.

Neither the spouse nor I are big believers in spirits or, for that matter, arbitrary emplacement of cleaning equipment. Nevertheless, the idea of earmarking a day to dead ancestors — even ones we had never met — kind of resonated. We lit the prescribed fourteen lamps in the evening. (I had pedantically advanced, it should have been twenty-eight instead — to cover both sides –, an unpersuasive argument as far as the spouse was concerned.) Meanwhile, the fourteen shaak will have to wait for next year, given the near-impossibility of finding more than half of the greens here, especially on the fly.

In Bangla, whenever you feel the urge to hyperbolically refer to your ancestors — the whole lot — you say choddo purush (fourteen generations). That’s a lot of ancestors, numerically. Even if you only consider your parents (2^1 = 2), grandparents (2^2 = 4), great-grandparents (2^3 = 8) and so on — setting uncles and aunts and variants thereof aside — fourteen generations is almost 33,000 people (32,766, to be precise).

This is very basic arithmetic, how geometric series works. But it is, also, extremely striking. If you think about it.

These 32,766 people — for me, beginning with those who lived in Mughal India — have contributed significantly to who I am today, to my totality. Despite what Steven Pinker has termed as the modern denial of human nature, genes matter. But also equally, and as part of our dual inheritance, it is lived experience and norms that are passed on from parents to their children that shapes, even in — especially in — breach. My mother’s contagious enthusiasm and my father’s probing, inward-looking, outlook, are, in large measure, why I am often carried away by the new, even as a part of me worries about what that may entail.

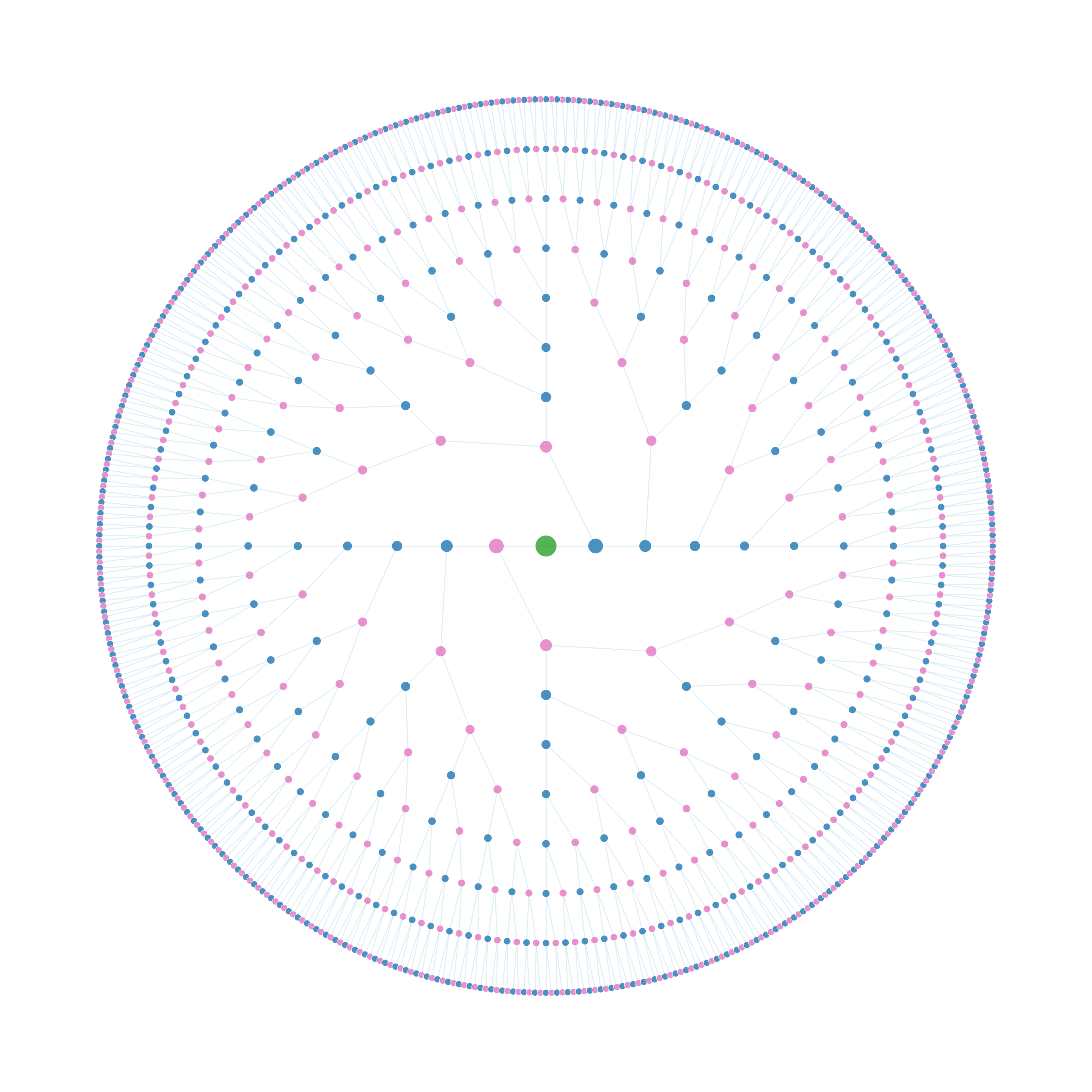

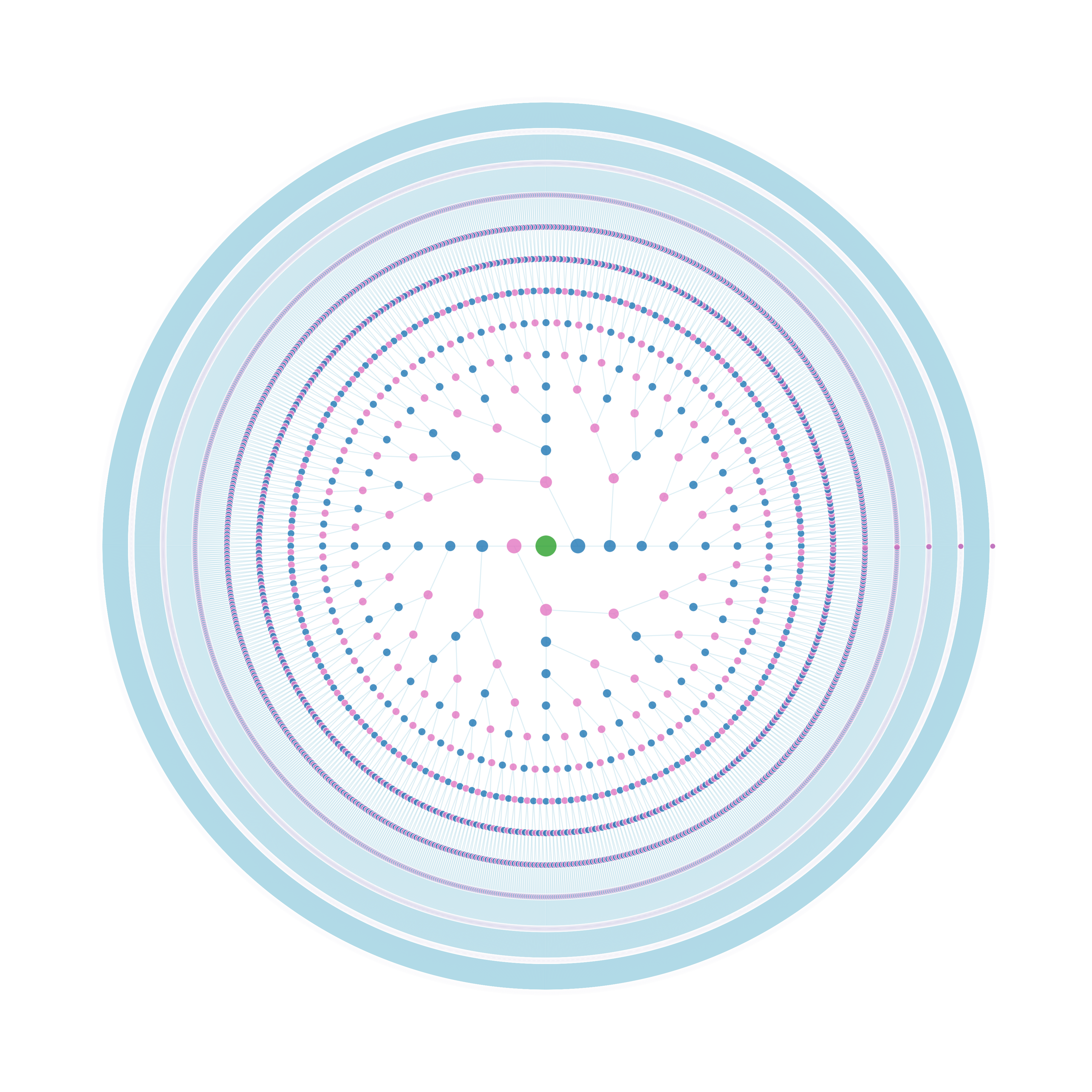

A picture helps us visualise the web of what we may owe our ancestors, if nothing as an aid in reflection.

Here’s one I whipped up using Python’s networkx library, with a defined layout that puts generations in concentric circles. (Evolutionary trees are sometimes depicted in roughly similar fashion.) Male parents are blue nodes; female pink. Any given node (child) in the network will be connected to one male and one female node (parents) through edges (light blue). The green node in the centre is you. Node sizes become smaller as we go back in time.

Let’s start with nine generations.

And, here’s fourteen generations, your choddo purush (albeit defined narrowly).

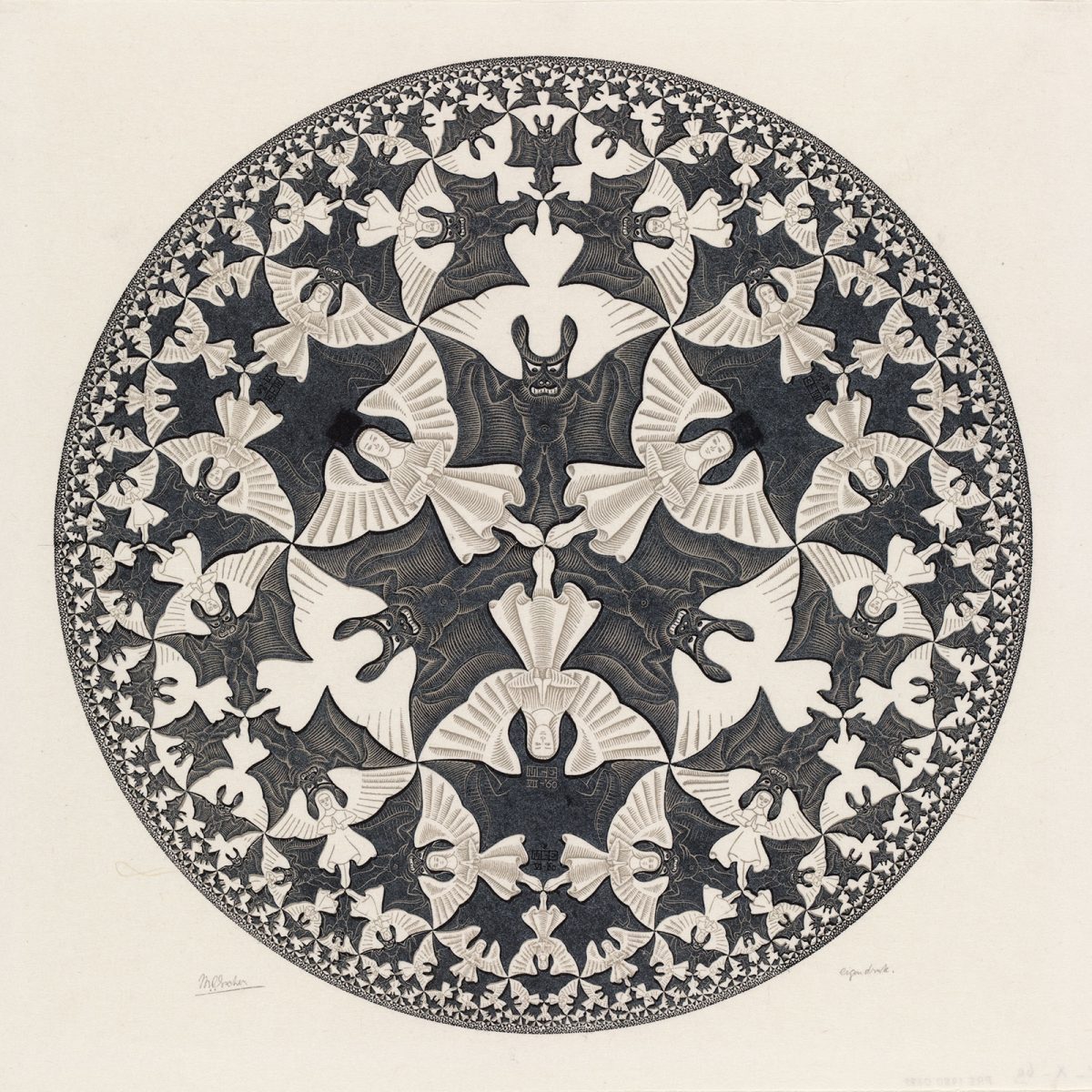

For reasons that are not completely clear to me, this reminds me of Dutch artist M.C. Escher’s “circle limit” series of woodcuts. The vagueness of the resemblance is irritating, more so given that while Escher drew significantly from hyperbolic geometry — aided by the great geometer H.S.M. Coxeter — ours is an extremely simple representation, a plain network created by a simple rule, laid out in a specific way.

Escher’s woodcut is about good and evil complimenting each other, stretching all the way to infinity, angels and devils becoming smaller and smaller as we reach for the boundary of the Poincaré disk.

So, perhaps the reason why I sense a similarity is because the simple genealogical tree and Escher’s woodcuts both depict the innumerable and distant radiating inward, complimenting each other, amplified in appearance — and in appearance alone?

But the centre is illusory in Escher, inconsequential, existing solely to visually enforce a sense of symmetry. Having admitted the conceptual congruence, should we, therefore, not consider the centre in our ancestral network — us — similarly?